REST (Representational State Transfer) is one of the most widely adopted architectural styles for designing networked applications. Whether you’re preparing for a technical interview or looking to improve your API design skills, understanding REST API principles is essential. In this post, we’ll break down the core concepts of REST, discuss its fundamental constraints, provide practical examples, and summarize the overall ideas to reinforce your learning.

What is REST?

REST is an architectural style introduced by Roy Fielding in his doctoral dissertation. It is not a protocol but a set of constraints that, when applied to a networked system (typically web services), enable scalability, simplicity, and reliability. RESTful APIs leverage HTTP methods, URIs, and standard data formats like JSON or XML to facilitate communication between clients and servers.

Core REST Principles

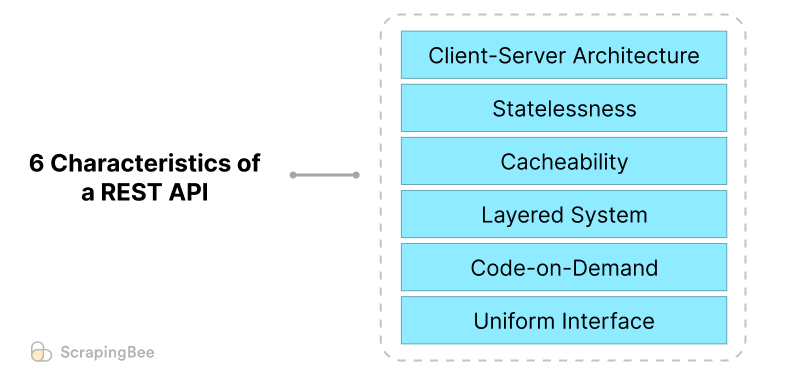

To fully understand REST, it is important to grasp its six guiding principles:

1. Client-Server Architecture

- Definition: Separates the user interface concerns from data storage concerns.

- Benefit: Improves portability of the user interface across different platforms and improves scalability by simplifying server components.

- Example: A mobile app (client) communicates with a remote server to fetch data rather than embedding data management logic on the device.

2. Statelessness

- Definition: Each request from the client to the server must contain all of the information needed to understand and process the request.

- Benefit: Enhances scalability since the server does not need to store session information between requests.

- Example: When a client makes a GET request to

/users/123, the server processes the request solely based on that request data without needing prior context.

3. Cacheability

- Definition: Responses must define themselves as cacheable or not, to prevent clients from reusing stale or inappropriate data in future requests.

- Benefit: Reduces client-server interactions, which enhances performance and scalability.

- Example: A GET request for a static resource like

/productsmay be cached by the client or an intermediary proxy.

4. Uniform Interface

- Definition: A standardized way of interacting with resources via a consistent set of rules.

- Benefits: Simplifies and decouples the architecture, enabling each part to evolve independently.

- Components of a Uniform Interface:

- Resource Identification: Each resource is identified by a unique URI (e.g.,

/books/1). - Resource Manipulation Through Representations: Clients interact with a resource by using its representation (typically JSON or XML).

- Self-descriptive Messages: Each message includes enough information to describe how to process the message.

- Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State (HATEOAS): Clients interact with the application entirely through hypermedia provided dynamically by server responses.

- Resource Identification: Each resource is identified by a unique URI (e.g.,

5. Layered System

- Definition: The client does not need to know whether it is connected directly to the end server or through an intermediary.

- Benefit: Enhances system scalability and security by allowing load balancing, caching, and proxy servers.

- Example: An API gateway or reverse proxy can manage requests between the client and various microservices without exposing internal architecture.

6. Code on Demand (Optional)

- Definition: Servers can temporarily extend or customize client functionality by transferring executable code.

- Benefit: Adds flexibility, though it is rarely used in practice.

- Example: Serving JavaScript to enhance client-side interactivity.

HTTP Methods and CRUD Operations

A well-designed RESTful API maps standard HTTP methods to CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations:

GET: Retrieve a resource.

Example:GET /users/123retrieves user 123’s data.POST: Create a new resource.

Example:POST /userscreates a new user with data provided in the request body.PUT: Update an existing resource.

Example:PUT /users/123updates user 123’s details with new data.DELETE: Remove a resource.

Example:DELETE /users/123deletes user 123 from the system.

These mappings help in creating an intuitive and predictable API design.

Practical Example: Building a Simple Task Management API

Imagine you are designing a simple RESTful API to manage tasks in a to-do list application. Here’s how you might map out the endpoints:

List All Tasks:

Request:GET /tasks

Response: JSON array of tasks.Create a New Task:

Request:POST /tasks

Request Body:{ "title": "Buy groceries", "description": "Milk, Bread, Eggs", "status": "pending" }

Response: The created task object with a unique id.

Retrieve a Specific Task:

- Request:

GET /tasks/{id} - Response: JSON object for the task with the given id.

- Request:

Update a Task:

Request:

PUT /tasks/{id}Request Body:

{ "title": "Buy groceries", "description": "Milk, Bread, Eggs, and Cheese", "status": "in-progress" }Response: The updated task object.

Delete a Task:

- Request:

DELETE /tasks/{id} - Response: Confirmation message or status code indicating deletion.

- Request:

Using cURL for Testing

Here are a couple of cURL examples to interact with your API:

Creating a New Task

curl -X POST http://api.example.com/tasks \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"title": "Buy groceries",

"description": "Milk, Bread, Eggs",

"status": "pending"

}'

Fetching a Task

curl -X GET http://api.example.com/tasks/1

These examples illustrate how you can interact with a RESTful API using HTTP methods that map to CRUD operations.

Best Practices for REST API Design

Consistent Naming Conventions: Use clear and consistent naming for endpoints (e.g., use plural nouns like /users).

- Versioning: Maintain API versions (e.g., /v1/users) to handle future changes without breaking existing integrations.

- Error Handling: Use standard HTTP status codes and provide informative error messages to help clients diagnose issues.

- Security: Implement authentication (e.g., OAuth, JWT) and authorization to protect sensitive data.

- Documentation: Provide clear, up-to-date documentation (e.g., using tools like Swagger or Postman collections) so that developers know how to use your API.

Summary

In this article, we covered the foundational principles of RESTful API design:

- Client-Server Architecture: Decoupling the client from the server.

- Statelessness: Ensuring each request is independent.

- Cacheability: Enhancing performance with cacheable responses.

- Uniform Interface: Standardizing interactions through HTTP.

- Layered System: Allowing intermediaries to improve scalability and security.

- Code on Demand: An optional principle for extending client functionality.

- We also explored how to map HTTP methods to CRUD operations and provided a practical example of building a simple task management API.